By Raymond Zhou

Last week, I was in Phoenix - not John McCain's homeplace in Arizona, but the small town in west Hunan province. I was invited to attend a forum for young writers and critics. I did not make the cut in age, but "young" is flexible in China and I've seen a 55-year-old placed in this category. Fortunately, most of the attendees happened to fall neatly into one age bracket: They were born in the 1970s, which automatically makes them "post-70ers", or "70-hou" in Chinese.

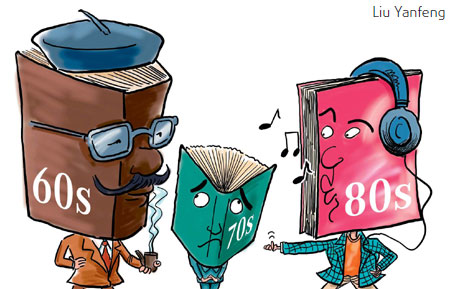

The editors and critics attending the function assured me that those present are among those with the biggest potential in Chinese literature. Yet they do not have name recognition beyond the coterie of like-minded creative writers. Of those active today, the biggest names, such as Yu Hua and Su Tong, are "60-hou", but "they mostly achieved fame while in their 30s", I was told. Another batch of writers favored by the mainstream media are the "80-hou", especially Han Han and Guo Jingming.

The "70-hou", or shall I say "30-something", seems to have fallen through the crevice of public attention. They don't have the heft of the earlier generations, nor the aptitude for market forces displayed amply by the younger generation. Overall, they feel more affinity with the "60-hou" because they have a sense of history and vaguely remember the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), said one.

While they are not yet enjoying the prestige of the "60-hou", they do not envy the commercialism of the "80-hou".

"Of course, I'd love to have a wider readership, but it has to come without compromising my integrity as a writer," said Xiu Zhengyang, a Hunan novelist born in 1977. Writers like Xiu make a clear distinction between fiction that aims to entertain and that with literary value. They call the latter "pure literature".

The platform for "pure literature" is comprised of dozens of publications put out by writers' associations in each province, many with a very small circulation.

People's Literature, one of the organizers of this forum, is a national brand. The country also has many literary awards, with the Lu Xun Award for short stories and novellas and the Mao Dun Award for novels. Many coastal provinces dangle other incentives to boost their images. Recently, the economically robust Zhejiang gave Mai Jia, who is also commercially successful, a house so that the province could claim him as one of its cultural assets.

A typical "70-hou" writer keeps a day job. Many are public servants, or minor officials, and others are newspaper and magazine editors. The 36-year-old Xie Zongyu is a policeman in Changsha. The job gives him an endless supply of unusual crime stories, which he can adapt into fiction.

He started by contributing to Zhiyin, a popular magazine that pays a good price for this kind of story. One day, he witnessed the bloated corpse of a young woman floating down the river. She was one of a pair of lovers who committed suicide because they could not see any future for their love. The man's body surfaced soon after drowning, but it took 10 days for the woman to be found. When people used a forklift that pierced into her body to drag it ashore, he could not help pondering the meaning of life.

Why should I spend my life churning out words that do not express the profundity of the human existence, he asked himself. He turned to serious writing, which often pays 100 yuan ($15) or less for every 1,000 Chinese characters. But he has no regrets. Unless you're a best-selling writer, he says, the money from creating literature does not make a difference to the quality of your material life.

However, people like Xie do care about fame and feel their writing can bring about change and gain them more respect. "What we want most is the recognition and applause from peers," said Zhe Gui, the 35-year-old from Wenzhou, Zhejiang province, a place with a pervasive business culture.

The ultimate goal, said Zhang Chu, a 34-year-old from Tangshan, Hebei province, who works at the local tax bureau in the daytime, is to "satisfy ourselves". Zhang's work probes the inner corners of the human mind, especially the dark recesses. In a sense, all writers focus on themselves, but "when we portray life in the countryside, our readers - our contemporaries - do not have the time and financial resources to buy our books," said Xie Zongyu. "But when the 80-hou took up writing there was already a sizeable demographic of urban consumers who could afford reading as a habit. Theirs is the first generation to benefit from the country's urbanization."

Yang Qingxiang, a 20-something literary critic, blames the "70-hou" for their failure to catch the public imagination: "Your personal growth coincides with the most dramatic changes of our country. Yet you do not attempt to reflect it in your writing. No wonder you cannot find a mass audience." Zhang Yueran, an 80-hou writer known for her talent as well as her beauty, sees it another way. In a recent article she expresses her "jealousy" for the 70-hou for their multilayered experiences. However, at the forum, she hanged out with members of her own generation.

The "70-hou" defend themselves by maintaining that it's not what you write, but how you write, that determines the value of a literary work. Case in point: Shen Congwen, one of the best novelists of the 20th century, a Phoenix native, never dwelled on the so-called big events. He dealt exquisitely with the lives of ordinary people, especially his hometown folk in the mountains between Hunan and Guizhou. Many of the widely acclaimed works of his time ebbed away, but Shen's fiction not only has survived the test of time, but shines brighter than ever.

Several young scribes see breakthroughs in writing techniques as their top priority. Only Zhe Gui says he wants to grapple with the "serious social ills" because "as a writer we have social responsibilities and we have to raise questions."

They seem to agree that the pendulum has stopped swinging between either content-centric or technique-centric and has reached equilibrium right now.

"I don't intend to reform the world. I'm aware of the futility of such efforts. I want to keep a certain distance with the outside world," says Xie Zongyu, the cop-author, whose day job forces him to stand face-to-face with the stark reality, especially the ugly things, of our era.

None of the authors who kept my company till the wee hours and answered my questions find it difficult getting published. It's the thunderous cheers that would make them household names that seem to be stubbornly elusive. Maybe it'll take some time for their work to sink in with the general public.

(China Daily 11/21/2008 page18)

我要看更多专栏文章