|

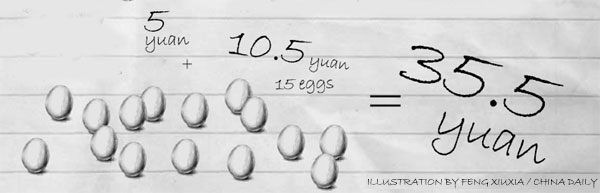

An expatriate in China looks at food from a different perspective, and takes part in a challenge that allows him only $1.50 a day for meals. Justin Ward tells us how and why he did it. As one of the millions of Americans caught up in foodie trend that had hit the nation over the past decade or so, it is hard for me to think of food as anything other than an indulgence. I enjoy cooking and eating so much that I tend to forget that there are 3 billion people in the world who do not view food as a luxury. For them, it means life. Even at the lowest end of the pay grade, expatriates in China make salaries that place them well within the ranks of the country's middle class. Some even get hardship allowance for living here, and the rest probably grumble that they should. Partly in an effort to examine my own privileged status as one of the so-called foreign experts, I decided to take part in the Live Below the Challenge, a global campaign that calls on people to eat on less than $1.50 a day in a show of solidarity with those living in poverty. Launched in May, the campaign was a cause du jour for celebrities, TV chefs and media personalities in the West. The public was treated to tales of anchormen living on off-brand bologna and movie stars giving up their lattes, but the perspective of a developing nation where a large proportion of the world's poor actually live was absent. At various times in history, China faced famine on a mass scale because of invasion, political upheaval, civil war, natural disasters and any other form of calamity imaginable. Now, there are the new problems of rising costs of living and the increasing gap between rich and poor. A fortunate outcome of the lean times is that the experience gave people tools to cope with the challenges. One is the traditional Chinese diet, which I followed rigorously to make it through the five days. Over the week, it became painfully clear why the Chinese words for breakfast, lunch and dinner are translated to "morning rice", "noon rice" and "evening rice", and why the word for "to eat" literally means "to eat rice". Rice became a large part of my own vocabulary and diet as well. I boiled it, fried it with green onions, made it into porridge with a hard-boiled egg for breakfast. And though I never really cared for them before, I learned to love noodles, the other Chinese staple. While most of my counterparts in Western countries were forced to cut out fresh vegetables for the week, I was able to afford some from the low-cost markets within walking distance from my apartment. Of course, calling them "fresh" might be a stretch. I usually found deals by going at the end of the day after the wares had already been picked over by early-rising retirees. My breakfast of rice porridge, and my lunch of noodles with slices of carrot and bean sprouts cost so little that I was left on most days with enough in the budget to afford a couple of cucumbers or tomatoes and eggs. Striving not to waste anything made me realize how much I had been wasting in the past. Everything that was left from a meal I packaged into containers and reused. Yesterday's soup and rice joined forces to become today's porridge. I was able to make it through the week without becoming miserable. Sure, I bemoaned the lack of ice cream and I began to miss the convenience of food that I did not have to cook myself, but in the end, it was not all that bad. In a way, it was enjoyable thinking up creative ways to push the boundaries of the standard of living to which I am accustomed. Poverty has many dimensions, and the cost of food is just one. This week has given me a new take on the value of food. My usual breakfast is at least 3 yuan (49 cents). And I often spend more than my entire food budget for the challenge just for the delivery fee of the food I order in. Before I began, my idea of hardship, as an expat, was lack of access to deli meat and tortillas. While I cannot say I know what it is like to live in poverty now, I think I am one step closer to knowing how little I really know. |

作为一个美国人,我深受过去几十年来美食主义盛行的影响。对于我来说,食物不是别的,就是享受。我如此享受做饭做菜、吃吃喝喝,以致于有时候我都快忘记了,在这个世界上,不能享受食物的乐趣的人有300万。于他们,食物仅仅是生存所需。 即使处于薪酬等级末端,在中国的外国人依然可以赚到足够多钱,使他们过上中产阶级的生活。有些人甚至还能得到艰苦生活条件津贴,而那些没得到的,也许都在嘀咕着为什么自己没有津贴。 部分为了好好审视一下所谓的“外国专家”身份带给我的某种特权地位,我最近决定参加一项“最低生存挑战”活动。这是一项全球性的活动,号召人们每天只花1.5美元(大概9.1元人民币)在食物上,以表示对过着贫困生活的人们的声援。 这项活动5月份启动,一时在西方吸引了很多明星、美食节目的大厨和媒体人士参与。公众借此享受到很多名人的轶闻趣事,诸如(为了省钱)某主持人吃杂牌红肠,那些电影明星们放弃了拿铁咖啡,不过,在中国这样一个生活着世界上很大比例的贫困人口的发展中国家,却极少有这类活动。 历史上,中国常常因为外族入侵、政局动荡、内战、自然灾害和其他意想不到的灾难而发生严重饥荒,而现在中国人面临的问题在于日益增加的生活成本和越来越大的贫富差距。 也许是福祸相依,从困难时期,中国人获得了应对饥饿挑战的经验,中餐就是其中之一。在过去的5天里,我也是严格依靠中餐果腹。 过去一周,我从痛苦经验中明白了,为什么中文里一日三餐被称作早饭、中饭、晚饭,为什么中文里用“吃饭”这个词。 “米饭”是我这几天用的最多的词,米饭也是我吃的最多的东西。我煮米饭,用葱炒米饭,还把米做成粥,配着白水煮鸡蛋做早餐。 面条是以前我从来不曾留意中国的另一种主食,如今我也变得热爱面条了。 当西方国家里参加这个挑战活动的人们不得忍痛舍弃新鲜蔬菜,我却可以从距离我的公寓几步路远的廉价菜市场买回来新鲜蔬菜。当然了,说我买回来的是新鲜蔬菜貌似有点牵强。我通常在晚上去菜市场,这个时候的菜便宜些,但是最新鲜的已经被很早就起床去菜市场的大爷大妈们挑走了。 我早饭就吃大米粥,午饭吃胡萝卜豆芽面,这些材料非常便宜,大多数日子里,我还能剩点钱买点黄瓜或者西红柿、鸡蛋。 为了避免挨饿,我不敢浪费任何东西,这让我意识到过去我多么的铺张浪费。 每一餐吃剩的我都保存起来,留着再吃。昨天剩的汤和米饭第二天鼓捣到一起就成了今天的粥。 经过努力,过去的一周里我活下来了,还过得不太悲惨。当然了,不能吃冰欺凌,我特别哀怨,每天自己做饭,我甚至开始怀念方便食品。不过,说到底,我过得还不错。 在某种程度上,为了尽可能贴近我平时享受到的生活水准不得不绞尽脑汁,这点我还挺享受的。 贫穷有多面性,食物成本仅是其中之一。 这一个周,我重新认识到了食物的价值。周三的时候,我犒劳自己,吃了一个价值一块五的包子。平时,我的早餐至少需要三块钱,而且我常常叫外卖,仅仅外卖服务费就超过这个活动规定的食物预算。 在参加这个活动之前,作为一个外国人,我想象的困顿生活仅仅在于没有熟肉和玉米饼。现在,我也不能说我完全知道生活在贫困之中是什么样,但是对于我是多么的无知,我想我比过去知道的多了一点。 (作者:Justin Ward 编译:刘志华) |