|

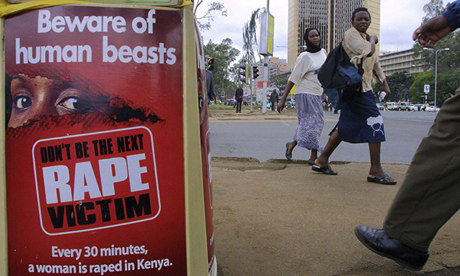

Funerals can be lengthy affairs in western Kenya, and Liz, a 16-year-old schoolgirl, was out late at a wake for her grandfather that had stretched into the evening. She was on her way home when she recognised some familiar and unfriendly faces in the darkness. She knew instantly that the six men in front of her meant her harm. A tall girl, she tried to run. When they caught up with her, she tried to fight. Her attackers, thought to be aged between 16 and 20, began by punching and kicking her. After she was hurt too badly to resist, they took it in turns to rape her. The problem was that the teenager would not submit quietly: she kept screaming. When they had finished with the girl, they dragged her to a deep pit-latrine nearby and threw her inside. But despite her horrendous injuries and a fall of nearly 12ft (3.6m), Liz managed to find the earthen steps used by the workers who dug the latrine to get out. As she pulled her broken body up the steps, villagers who had heard her cries found her. They quickly raised a mob to give chase. The schoolgirl knew some of the men who had raped her and started shouting their names. The villagers managed to find three of Liz's attackers and frogmarched them to the police outpost in the village of Tingolo, in Kenya's north-western county of Busia. The officers arrested the trio for assault and promised the girl's angry neighbours that the men would be punished. At daybreak, the rapists were handed curved machetes, known as "slashers", and told to cut grass in the police compound. Duly punished, they were sent home. The morning after the attack, Liz (not her real name) was taken to a dispensary, a rudimentary pharmacy that is the closest much of rural Kenya gets to a clinic, where she was given antibiotics and paracetamol. It was only when she found that she still could not walk, a week later, that her mother sold their chickens – the family's only source of income – and took her to a medical clinic in the nearest town. The doctor ignored the fact that she was doubly incontinent and told her she needed physiotherapy. Her condition worsened and her mother leased the family's land for about £60 – effectively mortgaging their home – to get her to the nearest big town, Kakamega, where she was eventually diagnosed with a fistula and damage to her spinal cord. This appalling, tragic tale would never have reached the outside world had it not been for the outrage of Jared Momanyi, the director of one of a handful of Kenyan clinics that specialise in the treatment of victims of sexual violence, to which Liz was eventually referred. He called a young reporter at the Daily Nationin the capital, Nairobi, who had previously written a story about the facility in Eldoret, a town perched on the western side of Kenya's Great Rift Valley. "It troubled me so much I needed to take it head on and tell the world," he said. "This was an attempted murder and it's not an isolated case; it's one among many." When the Nation's Njeri Rugene visited Liz more than three months after the 26 June gang rape, she found a broken, traumatised girl in a wheelchair. The story Rugene wrote helped raise £4,000 to pay for an operation to repair Liz's internal injuries, the first of two procedures the girl will need to have any chance of controlling her bladder and bowels or walking again. What has made the teenager's trauma even worse is that her assailants are still free. "She can't understand why people keep coming to ask questions but those men don't get arrested," said Rugene. Three of those who raped Liz are pupils at schools near her own and police have had the names of all six attackers since 27 June. After stories appeared in local newspapers, officers were finally sent to arrest those still in school. Teachers at one of the schools asked if the arrests could be postponed to allow them to take part in exams. The request was granted and police claimed afterwards that they were "tricked" by the teachers, who helped the pupils go into hiding. Mary Mahoka, a social worker with a local child protection organisation, said cases such as Liz's were the product of entrenched chauvinism in her home area of Busia, an impoverished county close to the shore of Lake Victoria. Polygamy was widely practised and girls were not valued by the community, she said. When she first started to work with rape victims in 1998, she found that perpetrators would pay for their crime by handing over a goat or a bag of maize to the girl's parents. Last week, Mahoka was helping a six-year-old girl who had been sexually assaulted by a man in his 20s. "It's happening every day, but often it's not reported," she said. Mahoka, whose organisation is partly funded by UK aid, has to disguise the nature of her group's work, calling it "rural education and economic enhancement" so as not to provoke hostility among traditionalists in the community. She has investigated the gang rape and says it was not a chance occurrence: "Liz had rejected advances from one of the boys, so he brought his friends to discipline her." After reading about Liz's ordeal, Nebila Abdulmelik, a women's rights activist in Nairobi, launched an online petition with the international campaign group Avaaz that has attracted more than 660,000 signatures. "Letting rapists walk free after making them cut grass has to be the world's worst punishment for rape," she said. "There is a silent epidemic in Kenya. It's not as loud as in Congo or South Africa, but the statistics are high." As many as eight out of 10 Kenyan women have experienced physical violence and/or abuse during childhood. A report from Kenya's national commission on human rights in 2006 found that a girl or woman is raped every 30 minutes. Orchestrating rape is also among the charges facing Kenya's president, Uhuru Kenyatta, who goes on trial on 12 November at the international criminal court accused of organising the violence that killed at least 1,300 people after a 2007 disputed election. Abdulmelik notes that, under Kenya's Sexual Offences Act, Liz's assailants should face prison sentences of not less than 15 years. The same legislation stipulates that the expenses incurred by victims of such attacks, including surgery and counselling, should be borne by the state. "This is the government's responsibility," she said. "There is impunity from top to bottom, and meanwhile our president takes an entourage to the Hague at taxpayers' expense." Avaaz and the African Women's Development and Communication Network (Femnet), of which Abdulmelik is a member, plan to picket the ministry of justice and police headquarters in Nairobi on Wednesday, where volunteers will cut the grass in protest at the handling of Liz's case. The outcry over the fate of the 16-year-old last week prompted Kenya's director of public prosecutions, Keriako Tobiko, to order the arrest of the six suspects and promise an inquiry into police failures. However, the investigating officer in Busia, Shadrack Bundi, said he had received no such directive and could not take any further action. Rasna Warah, a Kenyan commentator, said women were being failed by the country's leaders, male and female, who often left it to foreign-funded NGOs to raise awareness. "The Busia rape case is symptomatic of our society's attitudes towards women. Violence against women has become so normalised it almost constitutes a sort of 'femicide'." |

在肯尼亚西部,葬礼是一件很冗长的事务。天色有些晚了,16岁少女利兹还在外面,因为她去参加她祖父的葬礼,葬礼一直持续到晚上。在她回家的路上,她在黑暗中突然认出了几张熟悉却不怎么友善的面孔。她立刻意识到,面前的这六个男子对她不怀好意。利兹个子很高。起先她试图逃跑,在他们抓住她后还试图反击。年龄大约在16岁到20岁的攻击者们开始对她拳打脚踢。等到利兹被打得无力反抗后,他们轮流强暴了她。然而这位少女没有那么容易屈服:她始终在尖叫。 施暴结束后,他们把女孩拽到附近的一个深坑边,并把她扔了下去。所幸的是,尽管利兹受伤很重,并从约4米高处摔下,她还是成功地找到了挖坑工人用过的东边的梯子并爬了出来。在她把受伤的身躯从坑里拖拽出来后,村民顺着她的哭叫声找到了她。 村民迅速组织起了一支小队追捕嫌犯。女生利兹认识施暴者中的几个,并开始大喊他们的名字。村民们成功抓到了攻击者中的三名,把他们押送到了村里的派出所。丁格洛村坐落在肯尼亚西北部的布希亚郡。警察们以袭击为名逮捕了这三人,并向愤怒的村民们保证这三人会受到惩罚。到了第二天,警察们给三位强奸犯分配了弯刀,俗称大砍刀,并要求他们在派出所院里除草。接受完所谓的“惩罚”,嫌犯就这样回家了。 事发第二天,化名利兹的少女被送往医务室,对大部分肯尼亚人来说,这种基本的药房是最接近诊所的东西了。在医务室,她被注射了抗生素和扑热息痛。一周后,利兹发现自己还是无法下地走路。直到这个时候,她母亲才变卖了家里唯一的收入来源——几只鸡,并带利兹到了最近的城镇上的门诊部。不顾她已经失禁的现实,医生告诉她她需要接受物理治疗。随着她的病情继续加重,她母亲把房子作为抵押,以60法郎的价格出租了家里的土地,并把利兹送到了最近的大城市,卡卡梅加。在那里,利兹终于被确诊为瘘管,并且脊髓严重受伤。 如果不是杰瑞德·摩曼伊大发雷霆,这一令人震惊的悲剧故事本可能永远不被外界所获知。杰瑞德是肯尼亚为所不多的几家专门治疗性暴力受害者的诊所负责人,最终利兹就是在他的诊所接受了治疗。他致电了首都内罗毕的国家日报的一位记者。这位记者此前刚刚对埃尔多雷特——一座栖息在东非大裂谷西缘的小城——的基础设施进行了报道。"这件事使我深受折磨,我必须把它提出来,让整个世界看到,"杰瑞德说,“这是一场蓄意谋杀,而且这并不是孤立事件,只不过是许多类似事件中的一个。” 距离1月26日的集体强奸事件三个月,当国家日报的妮里·茹真造访利兹时,她看到的是一个内心和身体都受到巨大损害的轮椅里的女孩。 与此同时,她的袭击者仍然逍遥法外,这无疑使得这个花季女孩的伤痛更加深重。茹真说:“她无法理解为什么人们总是来对她提出问题,而不去追捕那些施暴者。” 施暴者中有三名是她附近学校的学生,而在1月27日,警察就已经掌握了全部六名袭击者的名字。当地报纸对这一事件进行了报道后,警察终于对还在校的施暴者进行了逮捕。其中一所学校的老师甚至问,逮捕可否推迟到嫌犯完成考试之后进行。这一要求被允许了,而警察事后表示他们被老师“蒙骗”了,那些老师实则在帮助学生躲避追捕。 一所当地儿童保护组织的社工玛丽·毛卡称,像利兹这样的事件是布希亚根深蒂固的沙文主义的产物。布希亚是靠近维多利亚湖的一个贫穷地区。 她说,一夫多妻制在那里非常普遍,女性不被社会重视。1998年当她刚刚开始接触强奸受害者时,她发现对作恶者的惩罚只是对女孩家赔偿一只羊或是一袋玉米。 上周,毛卡帮助了一位被20多岁男人性侵的6岁小女孩。她说:“这种事每天都在发生,只不过往往没有被报道。” 毛卡所在组织的一部分资金来源是英国。这个组织不得不掩饰其工作实质,谎称之为“推进农村教育,增强经济基础”,才没有在当地传统主义者间引发仇恨。 她对这次集体强奸进行了调查,并表示这绝不是一次偶然事件。“利兹早前拒绝了其中一名嫌犯追求,对方于是伙同朋友对她进行报复。” 在报上读到了利兹遭受的折磨后,内罗毕的一位妇女权益运动者奈比拉·阿卜杜梅里联合国际运动组织Avaaz启动了一项网上签名活动,日前已收到超过66万个签名。“强奸犯在完成除草后逍遥法外,这简直是世界上对强奸犯最荒唐的惩罚,”她说。“在肯尼亚有一种无声的传染病。它不如在刚果或南非的那么受到重视,可是这里的统计数据非常的高。” 肯尼亚高达十分之八的妇女中都在童年时期经受过身体上的虐待。肯尼亚国家人权委员会2006年发布的一篇报告指出,每30分钟就有一个女孩或妇女被强暴。 策划强暴也是针对肯尼亚总统乌呼鲁•肯雅塔的一项指控。乌呼鲁•肯雅塔在11月12日在国际刑事法院接受了审判,原因是他被指控在2007年颇受争议的选举后组织了杀害至少1300人的暴力行为。 阿卜杜梅里写道,根据肯尼亚的性侵法案,利兹的攻击者应该面临不少于15年的监禁。这项法律还规定,这类攻击对受害者造成的手术治疗和心理辅导费用应由国家承担。她说:“这是政府的责任。免受惩罚这一风气在全国是从上到下的,然而与此同时我们的总统带着随从去了海牙,花的还是纳税人的钱。” Avaaz组织和阿卜杜梅里所在的非洲妇女发展和沟通网路计划在周三包围内罗毕的司法部和警察总局。志愿者将在有关部门门前割草以抗议对利兹侵犯者的处理手段。 上周对这位16岁少女命运的公众在抗议终于促使肯尼亚的检查局长特比克对六名嫌疑犯下达了逮捕令,并承诺会对警察工作的失败进行调查。然而,布希亚的调查官员邦迪表示他没有收到这样的指令,无法执行进一步行动。 一名肯尼亚评论员拉斯那·瓦拉称,妇女不受重视是国家领导人所致。这些领导人,无论男女,往往把提高公众意识的职责推到外资非政府组织上。“布希亚的强奸案是我们整个社会对待妇女态度的一个缩影。针对妇女的暴力行为变的如此常态化,甚至已经可以构成一个新词——谋杀女人罪。” 相关阅读 (译者 angelica021 编辑 丹妮) |