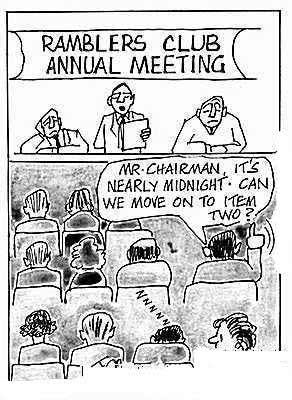

我参加过很多专题讨论会,不幸的是,它们大多空洞乏味,根本讨论不出什么东西。有的简直就成了一小撮人互相吹捧的“秀场”。而作为与会者的我从来都没有发言的机会,往往只能灰溜溜地提前退场。

By John Barry

冉洋洋 选注

I’ve been to a lot of panel discussions. I know what they’re like. When one hears the phrase panel discussion, one likes to think it’s a discussion that goes somewhere—like Plato’s Symposium[1]. This is not always the case. Panels frequently fail to adhere to the template of dialectical inquiry.[2] Attending a panel discussion is often about schmoozing[3], bringing your business card, drinking as much beer as possible, and recognizing at least a few people in the crowd. I have no problem with that part.

The problem occurs later on, when people are supposed to file into[4] a hall to listen to the panel discussion itself. I tend to find myself in the audience at these occasions. Maybe I shouldn’t, but I usually take that as an insult. I don’t assume that I know more than any of the people who get chosen to discuss things in panel form. I’m not more charismatic[5] than they are; my knowledge of various subjects is limited. But it strikes me that, even if I don’t know anything about, say, string theory[6], they never bothered to ask if I did.

I’m not sure why I keep showing up at these things. I always go expecting to learn something and expecting to eat something. And I always leave embittered, bursting with gotcha questions, and a little miffed at the fact that,[7] by being invited to a panel discussion and then told to sit in the audience, I’d actually been invited not to speak on the topic in question.

My wife asked me if I wanted to go to a panel discussion a week ago. She did it as a favor. She works in marketing. This particular panel discussion was conducted in honor of a design firm in our city of Baltimore. The firm, apparently, doesn’t exist anymore. But when it did, she told me, they represented the bold future of design in an age when design wasn’t bold. I went to this discussion with an open mind, assuming that I would be in front of a small colony of Mad Men, people with fire and vision, who had transformed the universe and built up the service-based American economy as we now know it.[8]

When my wife told me that she’d wrangled[9] tickets, I said I’d be glad to go. It sounded like they were the hottest tickets in town. I would learn something about design. I also had visions of a huge sideboard, loaded with hors d’oeuvres, jellies, compotes, and reasonably good wines.[10] I don’t know much about design, I don’t pretend to, and I wouldn’t even think of bringing my business card to a meeting like that. But I do know the difference between cheap wine and reasonably good wine.

On the night in question, we submitted our tickets at the desk. There was a large, buzzing[11] crowd of people I had never seen before. There was a large ice-filled bucket full of Amstel Light.[12] I walked immediately to the table required. There were also glasses, with wine, white and red. I was ready to double fist[13]—this really was the life —when the waiter behind the table put his hand on mine. Did he need an ID? I reached for my wallet. No, he said, I needed to buy a three-dollar ticket.

A three-dollar ticket, to pay for the open bar?

No, he said, to pay for a single drink.

What? Maybe I hadn’t heard right. A single drink? I could go two blocks[14] north, to any bar, I told him, and buy a National Bohemian for $2, and $1 on Friday nights. I could spend another 50 cents, and get a 24-ounce Budweiser.[15] And here, at this so-called panel, jammed in a crowd of people with strange glasses and weird haircuts, I was supposed to pay $3 per Amstel Light? Imperturbable[16], the bar person told me that, Yes, I had heard right, and that, fine, I was free to go to the Rendezvous. And could I move over[17] please, because there was a line forming behind me?

Finally, we filed into the chamber itself, a cavernous university auditorium, which boasted the most sophisticated sound system ever.[18] I’m assuming that it was sophisticated, because otherwise, there wouldn’t be much point in hanging corrugated steel[19] at weird angles above the stage. The rear seats were roped off, presumably to condense the audience a bit for the camera.[20] And on the stage itself was a large table, glowing under the dim spotlight, with six people behind it, all people who had been highly placed in the firm, most of them white-haired. The names of the respective people, presumably, in front of the respective people themselves.

“Without further ado[21]...”

That phrase was spoken immediately by a stammering ex-student who proceeded to read in barely audible tones what was apparently a tribute to one of the people on the panel.[22] The person he was paying a tribute to was a white-haired man with a huge, thick mustache, who was wandering behind him on the stage, shuffling[23], with this hands clasped behind his back. The tribute went on. It included a list of awards, which the person himself, whose name I forget, seemed to acknowledge with a self-deprecating shrug,[24] while the speaker, or payer of tribute, offered a self-deprecating assessment of his own tribute.

The man with the thick mustache eventually took over from the student and began to pay tribute to the payer of tribute. After a few grumpy[25] jokes, which were evidently intended to make it seem that he’d been dragged, kicking and screaming, to this conference, not because he didn’t want to be there, but because he didn’t deserve to be there, there was a long silence. I had lost track of what he was paying tribute to at that point. He had left a letter in his leather satchel[26], which, fortunately, he had had the presence of mind to bring with him on stage. He opened the satchel, and after burrowing around in it for a while, offered a murmured explanation to the audience,[27] which was sitting there in puzzlement. “This isn’t because I’m nervous,” he said. “It’s because there’s something in here I want to read which I can’t find.”

Eventually it was found, and the show was back on the road. What he had pulled out was an epistolary[28] tribute to the guy sitting closest to him at the table. His name was, well, let’s call him Ray. He had white hair, a close-cropped[29] beard, and he looked like he was in tears. Because of the tribute? No; Ray had weak eyes; the spotlight bothered him. Anyway, the laudatory[30] letter was read, acknowledging something—something good—about Ray, and then, once the man with the mustache had finished reading it, he placed it back in his leather satchel and asked Ray to comment. It was a softball question[31], but it was not a question that Ray chose to answer immediately.

Instead, Ray, with hands folded in front of him, began to pay tribute to the people next to him, people, he said, who were more deserving of being paid tribute to first than he was. The people at the table, some of whom were designers, seemed to nod their heads reluctantly, and modestly, the implication being that there were other, even more talented people, who deserved to be up there more than they did, and that it was absurd that those people couldn’t participate in the panel. The man on the far right of the table, who looked particularly frail, was motionless and seemed to have his chin pressed against his collar. He wasn’t responding in one way or another to what was being said.

That may have been the cue for the next topic of discussion: all those who deserved to be there at the table, but couldn’t, because they were dead. Ray listed the names, which flew by, and, as he listed them, he paid each one an effusive[32] tribute of one or two lines. None of the people named, of course, had the alternative of softening the compliments, or modestly deflecting them, or naming people for whom those generous appraisals were more deserved, because they were, in fact, dead.[33] Paradoxically, the fact that they weren’t around to deflate the praise with a well-chosen self-deprecating remark made them seem a little pompous.[34]

At about this time, I was beginning to feel that I had heard enough. This was, I understand, a design firm, but it could easily have been any other kind of firm, because nothing the panelists said offered any inkling[35] of what it was the Firm actually did. The assumption was that anybody who was fortunate enough to make it here already understood what this firm had done, even if it no longer existed. That was when I decided that, once again, I had come to the wrong panel discussion. With my wife, I joined the slow stream of early exiters.

Vocabulary

1. Plato’s Symposium: 柏拉图的《会饮篇》,主要记录了古希腊一群优秀的人物在一次酒宴之中的谈话,他们轮流对爱(Love)和爱神(Eros)进行赞颂。

2. template: 模板,典范;dialectic: 逻辑辩证的。

3. schmooze: 亲密交谈,闲聊。

4. file into: 鱼贯而入。

5. charismatic: 有魅力的,有感召力的。

6. string theory: 宇宙弦理论,一种基于存在宇宙弦的宇宙哲学理论。

7. 我总是悻悻离开,脑子里装满了刁难人的问题,并对以下情形有点儿生气。

8. 我带着开放的心态去参加这次讨论会,满以为自己将面对一小群“疯子”——他们有热情,有远见,曾改变这个世界的面貌,建立起我们今天所知的服务型美国经济体系。

9. wrangle: =wangle,设法弄到,用计获得。

10. 我还想象到了一个巨大的餐橱,里面摆满了开胃小菜、果子冻、果盘和相当不错的葡萄酒。

11. buzzing: 乱哄哄的,叽叽喳喳的。

12. bucket: 桶;Amstel Light: 一种淡味啤酒。

13. double fist: 双手开工,指一手抓一样东西。

14. block: 街区。

15. ounce: 盎司;Budweiser: 百威啤酒。

16. imperturbable: 冷静的,沉着的。

17. move over: 挪动一下,让个地方。

18. chamber: 会议厅;cavernous: 大而深的;auditorium: 礼堂,会堂;boast: 拥有。

19. corrugated steel: 波纹钢,波纹钢板。

20. 后排座位被圈了起来,可能是为了让观众坐拢点,以便拍摄。

21. without further ado: 闲言少叙(开始正题)。

22. stammering: 结结巴巴的;audible: 听得见的;tribute: 称赞,颂词。

23. shuffle: 拖着脚走。

24. self-deprecating: 自嘲的,谦虚的;shrug: 耸肩(表示不当回事或满不在乎等)。

25. grumpy joke: 指让人感觉不爽的笑话。

26. satchel:(有长背带和翻盖的)书包。

27. burrow: 翻寻;murmur: 低语,嘟哝。

28. epistolary: 书信体的。

29. close-cropped: 剪得很短的。

30. laudatory: 颂扬的。

31. softball: 无关痛痒的。

32. effusive: 热情洋溢的。

33. deflect:(使)转向;appraisal: 评价。

34. paradoxically: 看似荒谬地;deflate: 减缓,此处为自谦;pompous: 自大的,自负的。

35. inkling: 粗浅的认识,暗示。

(来源:英语学习杂志)