|

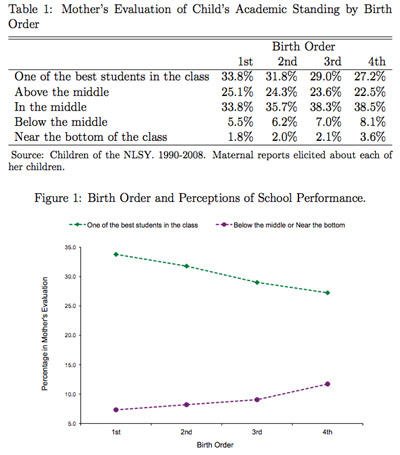

"Those born earlier perform better in school"—and according to a new study, it's because of the parents. Moms and dads simply go easy on their later-born kids, according to data analyzed by economists V. Joseph Hotz and Juan Pantano, and as a result, first-born children tend to receive both the best parenting and the best grades. The first thing to say about a study like this is that lots of readers will reflexively disagree with the assumption. With kids, as with anything, shouldn't practice make perfect? Don't parents get richer into their 30s and 40s, providing for better child-rearing resources? I'm a first child, myself, well-known within the family for being unorganized, forgetful, periodically disheveled, and persistently caught day-dreaming in the middle of conversations. For this reason, I've put stock in what you might call the First Pancake Theory of Parenting. In short: First pancakes tend to come out a little funny, and, well, so did I. And so do many first-borns. But international surveys of birth orders and behavior (which might have offered me an empirical excuse to behave this way) aren't doing me any favors. First borns around the world, it turns out, have higher IQs, perform better in school, and are considered more accomplished by their parents. Looking at parent evaluations of children from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth in 1979, the researchers found that mothers are much more likely to see their first children as high-achievers. They regard their subsequent children as considerably more average in their class (see table and chart below).

Let's briefly count off and nickname some of the leading older-kids-are-smarter theories reviewed by the economists, which push back against the principle of first pancakes. 1) The Divided-Attention Theory: Earlier-born siblings enjoy more time, care and attention than later-born siblings because attention is divided between fewer kids. 2) The Bad-Genes Theory:The strong evidence of higher IQs among first children leads some to believe that later kids are receiving diminished "genetic endowment." 3) The I've-Had-It-With-Kids! Theory: Some parents decide to stop having more children after a difficult experience raising one. In that case, the poorer performance of later children isn't genetic, so much as selection bias: Some parents keep having children until they have one that's so problematic it makes them say "enough." 4) The No-One-to-Teach Theory: This is the idea that older siblings benefit from the ability to teach their younger brothers and sisters. Building these teaching skills helps them build learning skills that makes them better in school. 5) The Divorce Theory: Family crises like divorce are far more likely to happen after the first child is born (first marriage, then divorce, then a first child is not a common sequence) and they can disrupt later kids' upbringing. 6) The Lazy-Parent Theory: The general idea here is that first-time parents, scared of messing up their new human, commit to memory the first chapter of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Motherbut by the second or third child, they've majorly chilled out. Hotz and Pantano settle close to Theory (6). Parents are more likely to make strict rules (about, e.g., TV-watching) and be intimately involved in the academic performance of their first children, according to survey data. They're also more likely to punish their first child's bad grades. Hotz and Pantano say moms and dads start tough and go soft to establish a "reputation" within their household for being strict—a reputation they hope will trickle down to the younger siblings who will be too respectful to misbehave later on. The theory is interesting but not entirely persuasive. First it seems nearly-impossible to test. The survey data is much better at showing that parents chill out as they have more kids than at showing that parents chill out because they're explicitly establishing a reputation for strictness. Nothing in the paper seems to argue against the simpler idea that parents seem to go soft on later kids because raising four children with the same level of attention you'd afford a single child is utterly exhausting. What's more, if later-born children turn out to be less academically capable than their older simblings, it suggests that the economists' reputation theory is failing in families across the country.

|

根据一个新调查显示“家庭中更早出生的孩子一般会比他们的弟弟妹妹在学校里表现得好”,并且原因有可能就在于他们的父母。 根据经济学家约瑟夫霍茨和胡安分析得知父母在照顾第二个孩子时总是更得心应手,不像第一个孩子时那么紧张和小心翼翼。因此,家庭中长子总是会受到父母更精心的照顾并且在学校中也能得到很好的成绩。 一看到这个命题的研究,大多数读者一定会对其表示质疑。对于照顾孩子或是其他的事情来说,难道不是越来越熟练吗?父母从三十到四十的过程中,难道不是越来越富有,并且所提供给孩子的物质条件不是会越来越好吗?我是长子,我自己在家庭中开始时总是被照顾得不是太有条理,甚至有些凌乱。甚至在与父母沟通交流中有一种不真实的感觉。就是因为这个原因,我相信你所说的这个关于父母的“第一个煎饼”的理论,也就是说,我们在第一次做煎饼时,总是手忙脚乱的。就像我当时被我的父母所照顾的时候一样。我想其他那些跟我一样在家里是第一个孩子也是一样的感受吧。 但是根据非常可靠的国际出生调查表中所显示的数据消息,跟我的预期是不一样的。世界上出生的第一个孩子,据调查来看,相比其他的孩子,都有更高的智商,并且通常在学校里能表现的更好,现在让我们看看1979年关于父母对于孩子表现的纵向数据,调查者发现母亲都偏向认为她们的第一个孩子的能力更好,或是更希望她们的第一个孩子能够更有能力,或是她们认为她们的幼子在学校里大多表现得一般般。(详情看下面的图表) 图表一:母亲对出生顺序不同的孩子在学校的表现情况的评估 出生顺序 第一个 第二个 第三个 第四个 最好 33.8% 31.8% 29.0% 27.2% 较好 25.1% 24.3% 23.6% 22.5% 中等 33.8% 35.7% 38.3% 38.5% 中下 5.5% 6.2% 7.0% 8.1% 较差 1.8% 2.0% 2.1% 3.6% 资料数据来源:全国青年纵向调查(1990-2008)中关于母亲对她各个孩子的评估。 数据一:出生顺序与学校表现的关系 总之就是据母亲来看,自己孩子中年长的孩子在学校的表现比年幼的孩子要更好。 1.分散注意力的理论:年长的孩子会享受到更多的照顾和疼爱相比于年幼的孩子,因为家长的注意力或是疼爱会被较为年幼的孩子所分散。 2.基因不好理论:由于一些强有力的证据表明,一些人趋向于相信第一个孩子智商更高并且年幼的孩子的遗传基因没有第一个孩子所接收得好。 3.过多理论:一些父母在经历过第一个孩子辛苦的养育经历以后会不太再想要孩子,并且就是因为那样,年幼的孩子在她们心里不如第一个孩子其实并不是基因问题而是她们的偏好问题,一些家长甚至于不会想要很多的孩子除非是他们的孩子已经出现了问题而迫使她们再去生养小孩,否则的话,他们真的是会觉得孩子过多。 4.自学理论:年长的孩子在家庭里总是充当老大的角色,她们总是倾向于照顾年幼的弟弟妹妹,而从小被弟弟妹妹所依赖的思想会带到学校中去,所以他们在学校里也倾向于表现得很棒,做弟弟妹妹的榜样。 5.离婚理论:家庭危机就像离婚一样大多数是在孩子出生以后(结婚然后离婚,争取抚养权的压力不在第一个孩子上,)如果生的孩子过多的话,他们也许会更有压力而离婚。 6.懒父母理论:一些第一次当父母的人很怕自己会陷入那些很混乱的境地,就像那个虎妈一样,被第二个第三个孩子所“折磨”得很累,她们倾向于尽心培养一个孩子。 霍茨也补充了一些理论。父母总是对第一个孩子要求的比较严格:例如关于看电视的规定啊 这对孩子在学校的表现是很有关系的,并且有数据表明,他们甚至还会对孩子的成绩不好做出惩罚。父母喜欢在家庭中营造一种氛围——他们希望在她们年幼孩子的耳濡目染中灌输荣誉感和是非观。哪些事情不能做而哪些事情是可以受到表扬的。 这样的理论是有趣的但并不是很具有说服力的,首先这个理论实在不好证明可信度。调查数据也只能显示父母在孩子的培养过程中会表的越来越冷静熟练,二所谓的冷静熟练也仅仅就是他们会直接建立一种明确的奖惩制度。这份数据不能表明对于培养一个孩子所付出的的辛苦可以等同于培养四个。显而易见,培养四个优秀的孩子要比一个累得多。更多的是,第一个孩子比其他的孩子更聪明的理论也在暗示一些经济学家所谓的“奖惩制度”在现如今的家庭中也是说不通的。 相关阅读 (译者 宁文菁 编辑 丹妮) |